Introduction to Feature Toggles

A Feature Toggle is a mechanism for placing two alternative implementations of some piece of functionality side-by-side in a deployable unit of code, along with the ability to toggle between which of the two implementations are used.

Feature Toggles are a useful and broadly applicable tool. As such their usage within an organization very often grows to encompass quite a wide variety of use cases such as hiding unfinished features, controlling feature release, and A/B testing, to name just a few. There are also various ways to implement and manage toggles. It is important to take into account the intended purpose for a toggle when choosing the mechanisms to implement and manage that toggle. It’s common when first using Feature Toggles to manage them all the same way, but as we’ll see there are significant benefits in distinguishing the different types of toggles and managing each toggle appropriate to its usage.

An example toggle

Let’s look at a simple example of how a feature toggle might be used. Pretend that we’re building a simulation game and have been working on a new more efficient algorithm for reticulating splines (a key operation in our game). Our new algorithm is not quite ready for prime time so we don’t want to enable it for our paying customers just yet, but we do want to be able to test the algorithm in our staging environment. Here’s how we might use toggles to achieve that end:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

You can see that if the use-new-spline-algorithm feature is turned on we’ll use our new enhancedSplineReticulation() function, otherwise we’ll keep using the tried-and-true oldFashionedSplineReticulation(). You can imagine that in this case we have some mechanism so that featureIsEnabled("use-new-spline-algorithm") returns false when we’re running our program in our production environment but returns true in our staging environment. Thus we are able to ship both approaches in the same codebase and experiment with the new technique without having to commit to exposing it to our entire userbase just yet.

Terminology

In this example use-new-spline-algorithm is the Feature being toggled. The reticulateSplines function is the Toggle Point - a branch point where we decide between two codepaths based on the state of a specific toggle. The featureIsEnabled function is a Toggle Router - code which is responsible for determining whether a specific Feature should be considered On or Off (the Feature’s Toggle State). The Toggle Router will decide the Toggle State via some Toggle Configuration. More sophisticated Routers will also use extra Toggling Context information at the moment of invocation to determine the state of a toggle. Examples of extra Toggling Context might by which user is making a web request, or the presence of a specific HTTP Header.

Categories of Feature Toggles

As the number of Feature Toggles in use grows it becomes very beneficial to categorize toggles based on their intended purpose. This allows you to manage different categories of toggles appropriately. I break these Feature Toggle use cases down into the following categories:

Dev Toggles

When practicing Trunk-based Development we use Dev Toggles to allow us to commit incomplete features directly into trunk. The code path which exercises the incomplete feature is disabled via a Dev Toggle by default. Team members building or testing the feature can override the configuration as needed. Once development is complete the toggle is turned on, and then quickly removed. It’s quite common to use Dev Toggles as the control mechanism for a Branch By Abstraction.

Dev Toggles are created and controlled by developers on a team, and should be as short-lived as possible. The mechanism to control whether the toggle is on or off can be as simple as an #ifdef statement or a commented out method call. If a more sophisticated control mechanism is used it’s important to ensure that the toggle configuration flows through our Continuous Delivery pipeline as part of the deployment artifact. This ensures that we’re consistently exercising the same code paths as our artifact flow through environments on its way to production.

Release Toggles

With complex systems new feature development often spans multiple inter-related codebases. For example a new end-user feature may be dependent upon a new service API which in turn is dependent on the roll-out of some new caching infrastructure. Historically these dependencies tend to be managed by being batched into large, coordinated, “big bang” deployments where all the constituent changes involved in the new feature must all be released simultaneously, and successfully. This approach carries a large amount of coordination overhead and is absolutely fraught with risk.

We can mitigate this issue by having each team involved place their new functionality behind a Release Toggle. This decouples each team’s deployment process and allows individual teams to safely “turn on” their new functionality as and when the systems which that new functionality depends upon become available. This removes the need for coordinated deployments, with teams instead coordinating new feature release via re-configuration of their respective Release Toggles.

Product Toggles

A team which is practicing trunk-based development and deploying to production frequently loses the ability to use deployment as a way to control when a new feature is released to end-users. We can solve this by placing the user-facing aspects of new features behind a Product Toggle. End-users will now only see a new feature when the toggle is flipped on, putting control back in the hands of the person managing the product. Like Release Toggles, Product Toggles allow the act of deploying code for a new feature to be decoupled from the release of that feature.

A product manager can use this control for various ends. They might use it as a way to release a set of related features simultaneously, or to reduce the amount of new feature “fatigue” end-users face, or to synchronize feature release with an external marketing event.

A more sophisticated use of Product Toggles is a Canary Release, where a Product Toggle is turned on just for a small percentage of users - a “canary” cohort. This is done to verify that the new feature does not have a negative impact, usually measured by comparing key business metrics such as conversion rate or user engagement between the canary and control cohorts. This usage is very similar to the idea of Experiment Toggles used in Multivariate- or A/B-testing. The distinction is that a canary release is a safer way to release presumed-good code changes while a Multivariate experiment is just that - an experiment which was planned in advance with the express intention of confirming or denying a product hypothesis.

Experiment Toggles

These toggles are used to perform Multivariate or A/B testing. Each user of our system is placed into a cohort and at runtime our system will send a given user consistently down one code path or another based on which cohort they are in. By tracking the aggregate behaviour of different cohorts we can compare the effect of the two different code paths. This technique is commonly used to make data-driven optimizations to things such as the purchase flow of an ecommerce system, or the wording of a Call To Action button.

Experiment Toggles must be in place long enough to generate statistically significant results, and need to be consistently applied over their entire lifetime.

Permissioning Toggles

These toggles are used to change the features or product experience that certain users receive. For example we may have a set of “premium” features which we only toggle on for our paying customers. Or perhaps we have a set of “alpha” features which are only available to internal users and another set of “beta” features which are only available to internal users plus beta users. This technique of turning on new features for a set of preview users is sometimes refered to as Dark Launching. Personally I prefer the term Champagne Brunch - an early opportunity to ”drink your own champagne”. This is a similar pattern to the Canary Release used with Product Toggles. The distinction between the two is that a Canary Released feature is exposed to a statistically random cohort of users while a Dark Launched feature is exposed to a specifically selected set of users.

An important distinction between Permissioning Toggles and other types of toggles is that in some cases they may be extremely long-lived. This highlights why it’s so important to identify which category a specific toggle falls into. The engineering approach used to implement the Toggle Point of a Dev Toggle with a lifetime of a few days should be very different than the approach used for a Permissioning Toggle where that Toggle Point code may live in your codebase for several years.

Ops Toggles

These toggles are used to control operational aspects of our system’s behavior. We might introduce an Ops Toggle when rolling out a new feature which has unclear performance implications so that system operators can disable or degrade that feature quickly in production if needed.

Most Ops Toggles will be relatively short-lived - once confidence is gained in the operational aspects of a new feature the toggle should be retired. However it’s not uncommon for systems to have long-lived “Kill Switches” which allow operators of production systems to temporary degrade a non-vital feature of the system (e.g. a Product Recommendation panel in the home page) when the system is enduring unusually high load. I worked for an online retailer which maintained Ops Toggles that could intentionally disable many non-critical features in their website’s main purchasing flow just prior to a high-demand product launch. These sorts of long-lived Ops Toggles could be seen as a manually-managed Circuit Breaker.

Options for Managing Toggles

Fundamental to feature toggling is a Toggle Router - the mechanism for determining whether a feature is toggled on or off, and thus choosing between two different codepaths. That routing decision can be made with various degrees of sophistication from a simplistic scheme which can only be varied by a new code deploy through to a highly dynamic scheme which allows the toggle state to vary for each invocation of the router based on a variety of factors. Toggle Routers are controlled by Toggle Configuration, which can also be implemented in a variety of ways which vary from simple but static to complex but dynamic.

The complexity of the routing and configuration mechanisms should depend upon the category of toggle. Using a complex run-time mechanism when you’re working with simple short-lived Dev Toggles would be overkill. Conversely, a static approach which requires a redeployment (or a process restart) in order to toggle a feature on or off may not cut the mustard for an Ops Toggle that needs to be managed in an orchestrated way across a live production environment.

Let’s look at the various approaches available for managing Toggle Configuration, moving from less dynamic to more dynamic. Then we’ll discuss other aspects of Toggle Routing.

Hardcoded Toggle Configuration

The most basic technique - perhaps so basic as to not be considered a Feature Toggle - is to simply comment or uncomment blocks of code. For example:

1 2 3 4 | |

Slightly more sophisticated than the commenting approach is the use of a preprocessor’s #ifdef feature (if available).

Obviously these hardcoding mechanisms don’t allow dynamically re-configuring a toggle, making them only really suitable for Dev Toggles, and perhaps Product Toggles in some cases. Nevertheless, for simple situations this technique is perfectly suitable.

Parameterized Toggle Configuration

The build-time configuration provided by Hardcoded toggles isn’t dynamic enough for many Feature Toggle use cases. A simple approach which at least allows toggles to be re-configured without re-building an app or service is to specify Toggle Config via command-line arguments or environment variables. This is a simple and time-honored approach to toggling which has been around since well before anyone refered to the technique as Feature Toggling. However it comes with limitations. It can become unwieldy to coordinate configuration across a large number of processes, and changes to a toggle require either a re-deploy or at the very least a process restart (and probably privileged access to servers by the person re-configuring the toggle too).

Toggle Configuration File

Another option is to read Toggle Configuration from some sort of structured file. It’s quite common for this approach to start off with Toggle Configuration living as part of a more general application configuration file.

A naive Toggle Router implementation would re-read the file each time it needs to decide Toggle State, which is a very inefficient approach. More sophisticated routers will cache the Toggle Configuration, perhaps expiring the cache on a regular basis or when asked to do so via a SIGHUP or similar.

With a Toggle Configuration file you can now re-configure a toggle by simply changing that file rather than re-building application code itself. However, although you don’t need to re-build your app to toggle a feature in most cases you’ll probably still need an app re-deploy in order to re-configure a toggle.

Toggle Configuration in App DB

Using static files to manage toggle configuration becomes cumbersome once you reach a certain scale. Modifying configuration via files is relatively fiddly. Ensuring consistency across a fleet of servers becomes a challenge, making changes consistently even more so. In response to this many organizations move Toggle Configuration into some type of centralized store, often an existing application DB. This is usually accompanied by the build-out of some form of admin UI which allows system operators, testers and product managers to view and modify Features Toggles and their configuration.

As Toggle Routing is often required as part of responding to every system request this quickly becomes a read-intensive performance bottleneck. This is frequently combatted with the introduction of a memcached layer, plus perhaps a local in-memory cache.

Distributed Toggle Configuration

Using a general purpose DB which is already part of the system architecture to store toggle configuration is very common; it’s an obvious place to go once Feature Toggles are introduced and start to gain traction. However nowadays there are a breed of special-purpose hierarchical key-value stores which are a better fit for managing application configuration - services like Zookeeper, etcd, or Consul. These services form a distributed cluster which provides a shared source of environmental configuration for all nodes attached to the cluster. That configuration can be modified dynamically whenever required, with all nodes in the cluster automatically informed of the change. Managing Toggle Configuration using these systems means we can have Toggle Routers on each and every node in a fleet making decisions based on Toggle Configuration which is coordinated across the entire fleet.

Some of these systems (such as Consul) come with an admin UI which provides a basic way to manage Toggle Configuration. However at some point a small custom app for administering toggle config is usually created.

Dynamic Toggle Configuration vs. Continuous Delivery

Something to keep in mind when considering a configuration approach which is externalized from your deployable unit is that it introduces a second pathway for changes in your environment, besides your deployment pipeline. When something unexpected happens in your environment you no longer have a single source of changes to look to. You now need to consider both application deployments and configuration changes.

Configuration layering

One pattern that crops up very frequently with app configuration in general and feature toggling in particular is the concept of layering or overriding a base or default configuration with some more specific overrides. For instance a program might ship with a default configuration which is hardcoded but have some config which is overridden by an environment-specific configuration file and then some of that config might be overriden by a second instance-specific file. This approach makes it easier to see which configuration is specific to a particular environment or instance, but it also brings a risk of confusion - “That’s strange. Why is this feature showing as toggled on just for this one server?”.

Per-request toggle routing

So far we’ve been assumed that a routing decision can be made based entirely on a simple on/off toggle configuration. However more sophisticated categories of feature toggle require routers which use additional criteria (Toggle Context) when deciding toggle state. For example with Experiment Toggles a routing decision needs to take into account which Cohort a specific user has been placed in for a given experiment. Permissioning Toggles will usually be based on what organization a user belongs, and perhaps whether a user falls into a specific category or group (such as Administrators or Read-only Users) inside that organization. With web applications this additional Toggle Context comes in with each request, usually via HTTP cookies.

These more sophisticated routers also require a more complex Toggle Configuration. Beyond just configuring a feature as On or Off in an environment we now need to be able to express configuration such as a feature being available to a certain percentage of our users, or just to beta users, or just to Administrators.

As mentioned earlier, as soon as toggle routing becomes a per-request operation we must start taking performance into account. If any Toggles control access to sensitive features such as admin-only capabilities then we must also pay serious attention to the security of our approach.

Implementation Techniques

de-coupling decision points from decision logic

I’ve observed that the techniques used to implement and manage Feature Toggles in a codebase tend to evolve somewhat organically over time. This can lead to some rather messy code which becomes a chore to maintain.

One specific mistake I often see is to couple the place where a toggling decision is made (the Toggle Point) with the logic behind the decision (the Toggle Router). Let’s look at an example. We’re working on the next generation of our ecommerce system. One of our new features is to allow a user to easily cancel an order by clicking a link inside their order confirmation email. We’re using feature toggles to manage the rollout of all our next gen functionality. Our initial feature toggling implementation is like so:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | |

While generating the order confirmation email (aka invoice email) our InvoiceEmailler checks to see whether the "next-gen-ecomm" feature is enabled. If it is then the emailler adds some extra order cancellation content to the email.

While this looks like a reasonable approach, it’s very brittle. The decision on whether to include order cancellation functionality in our invoice emails is wired directly to that specific feature flag - using a magic string, no less. What happens if we’d like to turn on some parts of the next-gen functionality without exposing order cancellation? Or vice versa? What if we decide we’d like to only roll out order cancellation to certain users? It is quite common for these sort of “toggle scope” changes to occur as features are developed. It’s also common for these toggle points to proliferate throughout a codebase. With our current approach each toggle decision change will require trawling through all those toggle points which have spread through the codebase.

Happily, any problem in software can be solved by adding a layer of indirection. We can decouple a toggling decision point from the logic behind that decision like so:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 | |

We’ve introduced a FeatureDecisions object, which acts as a collection point for any feature toggle decision logic. We create a decision method on this object for each specific toggling decision in our code - in this case “should we include order cancellation functionality in our invoice email”. Right now that decision logic is trivial, but as that logic evolves we have a singular place to manage it. Whenever we want to modify the logic of that specific toggling decision we have a single place to go. We might want to modify the scope of the decision - for example which specific feature toggle controls the decision. Alternatively we might need to modify the reason for the decision - from being driven by a static feature toggle to being driven by an A/B experiment, or by an operational concern such as an outage in some of our order cancellation infrastructure. In all cases our invoice emailler can remain blissfully unaware of how or why that toggling decision is being made.

Inversion of Decision

In the previous example our invoice emailler was responsible for asking the feature toggle system how it show perform. This means our invoice emailler has one extra concept it needs to be aware of, and an extra module it is coupled to. This makes it harder to work with and think about in isolation, which includes making it harder to test. As Feature Toggling has a tendancy to become more and more prevalent in a system over time we would see more and more modules becoming coupled to the feature toggle system as a global dependency.

In software design we can often solve these coupling issues by applying Inversion of Control, including in this case. Here’s how we might de-couple our invoice emailler from our feature toggling system:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | |

Now, rather than our InvoiceEmailler reaching out to FeatureDecisions it has those decisions injected into it at construction time via a config object. We’ve also introduced a FeatureAwareFactory to centralize the creation of these decision-injected objects. This is a application of the general Dependency Injection pattern, and if a DI system were in play in our codebase then that would be a clean way to implement this approach.

Avoiding conditionals

In our examples so far our decision point has been implemented using an if statement. This might make sense for a simple, short-lived toggle. However point conditionals are not advised anywhere where you have several Toggle Points or where you expect the Toggle Point to live in the code for a while. A more maintainable alternative is to implement alternative codepaths using some sort of Strategy pattern:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 | |

Here we’re applying a Strategy pattern by allowing our invoice emailler to be configured with a content enhancement function. FeatureAwareFactory selects a strategy when creating the invoice emailler, guided by its FeatureDecision. If order cancellation should be in the email it passes in an enhancer function which adds that content to the email. Otherwise it passes in an identityFn enhancer - one which has no effect and simply passes the email back without modifications.

Working with feature-toggled systems

While feature toggling is certainly a helpful technique it does also bring additional complexity. There are a few techniques which can help make life easier when working with a feature-togggled system.

Expose current feature toggle configuration

It’s always been a good practice to embed build/version numbers into a deployed artifact and expose it somewhere so that a dev or tester can find out what specific code is running in a given environment. The same idea should be applied for feature toggles. Any system using feature toggles should expose some way for an operator to discover the current state of the toggle configuration. In an HTTP-oriented SOA system this is often accomplished via some sort of metadata API endpoint or endpoints. See for example Spring Boot’s ‘management’ endpoints.

Categorize your toggles

Feature Toggles usually become used for a variety of reasons. The motivation for a toggle has an impact on things like how long the toggle will be in place, how toggling decisions are made, and who configures the toggle in different examples. Although different categories of togggles are often implemented using the same technical architecture it is still a good idea to distinguish between these different categories when building management interfaces, rather then throwing them all together in a single UI. This allows each UI to be tailored for the toggle’s use case and the way those types of toggles are administered. Practically speaking this can also prevent incidents where a Product Manager inadvertantly flips a production system into a failover state, for example.

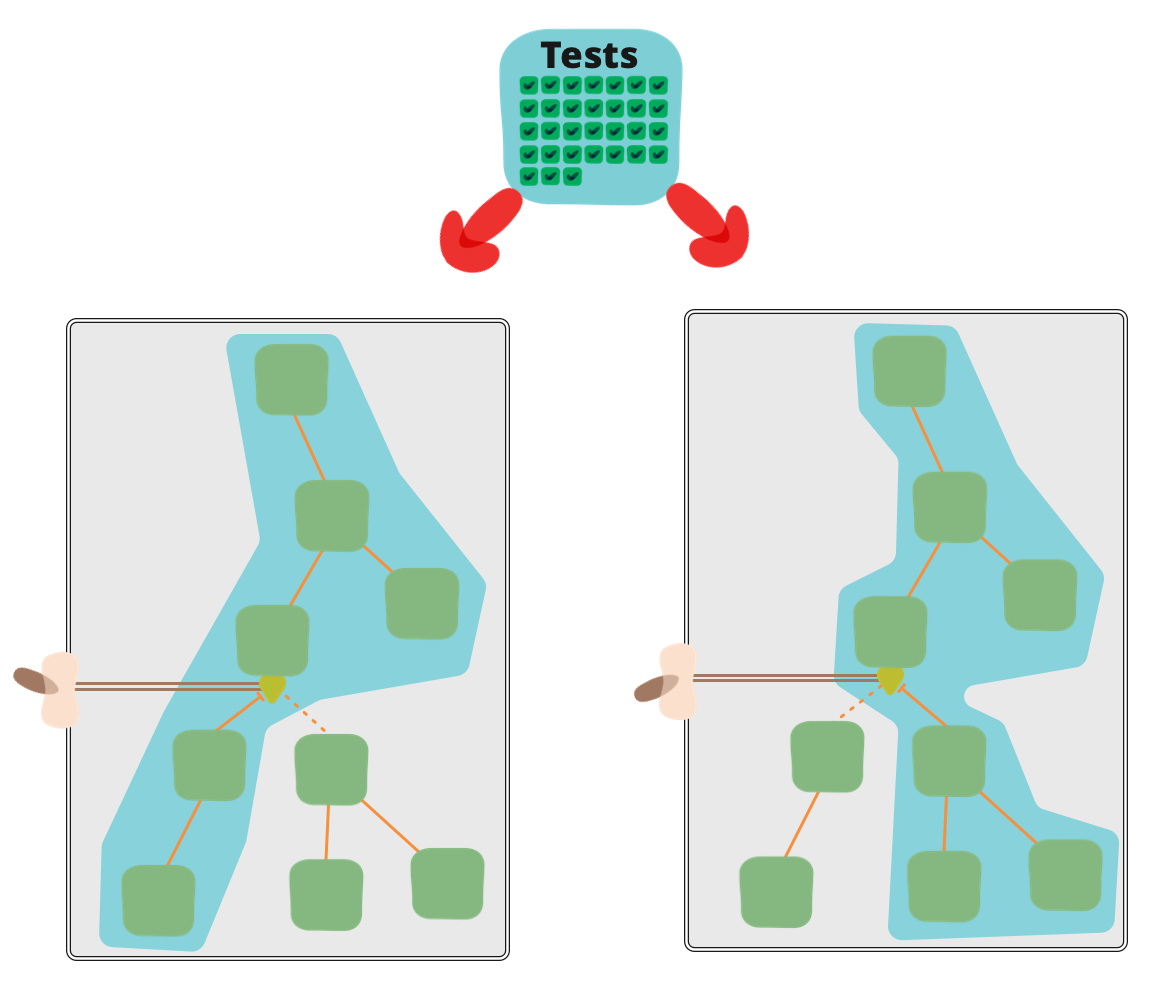

Feature Toggles introduce validation complexity

With feature-toggled systems our Continuous Delivery process becomes more complex since we’ll often need to test multiple codepaths for the same artifact as it moves through a CD pipeline. To illustrate why, imagine we are shipping a system which can either use a new optimized tax calculation algorithm if a toggle is on, or otherwise continue to use our existing algorithm. At the time that a given deployable artifact is moving through our CD pipeline we can’t know whether the toggle will be turned on or off in production - that’s the whole point of feature toggles after all. This means we must perform validation on our artifact both with the toggle flipped On and flipped Off.

If your feature toggle system doesn’t support runtime configuration then you may have to restart the process you’re testing in order to flip a toggle, or worse re-deploy an artifact into a testing environment. This can have a very detrimental effect on the cycle time of your validation process, which in turn impacts the all important feedback loop that CI provides. To avoid this issue consider exposing an endpoint which allows for dynamic in-memory re-configuration of a feature toggle. These types of override becomes even more necessary when you are using things like Experiment Toggles where it’s even more fiddly to exercise both paths of a toggle.

This ability to dynamically re-configure specific service instances is a very sharp tool. If used inappropriately they will cause a lot of pain and confusion in a production environment. As such this should only ever be used by automated tests, and possibly as part of manual exploratory testing and debugging. If there is a need for a more general-purpose toggle control mechanism for use in production environments it would be best built out using a grown-up distributed configuration system such as Consul or Zookeeper.

Per-request overrides

An alternative approach to a stateful in-memory override is to allow toggle state to be overridden on a per-request basis by way of a special query param, cookie, or HTTP header. This has a few advantages over providing a stateful override via a management endpoint. If a service is load-balanced you can still be confident that the override will be applied no matter which service instance you are hitting. You can also override toggles in a production environment without affecting other users, and you’re less likely to accidentally leave an override in place. If the per-request override mechanism uses persistent cookies then someone testing your system can configure their own custom set of toggle overrides which will remain consistently applied in their browser. The downside of this per-request approach is that it makes it a lot harder to prevent curious or malicious end-users from modifying feature toggles themselves. Some organizations may be uncomfortable with the idea that some unreleased features may be publically accessible to a sufficiently determined party. Cryptographically signing your override configuration should mostly alleviate this concern, but regardless this approach will increase the complexity - and attack surface - of your feature toggling system.

[FOOTNOTE] I elaborate on this technique for cookie-based overrides in this post and have also documented a ruby implementation open-sourced by myself and a ThoughtWorks colleague.

Where to place your toggle

Toggles at the edge

For categories of toggle which need per-request context (Experiment Toggles, Permissioning Toggles) it makes sense to place control for those toggles in the edge services of your system - i.e. the publically exposed web apps that present functionality to end users. Here is where your user’s individual requests first enter your domain and thus where you have the most context to make toggling decisions based on the user and their request. A side-benefit of placing toggle control at the edge of your system is that it keeps fiddly conditional toggling logic out of the core of your system.

Placing your toggles at the edges also makes sense when you are controlling access to new user-facing features which aren’t yet ready for launch (Product Toggles). In this context you can control access using a toggle which simply shows or hides UI elements. As an example, perhaps you are building the ability to log in to your application using Facebook but aren’t ready to roll it out to users just yet. The implementation of this feature may involve changes in various parts of your architecture, but you can control access to the feature with a simple feature toggle at the UI layer which hides the “Log in with Facebook” button. In these situations the bulk of the unreleased functionality itself is often not even hidden, it’s just discoverable to users.

Toggles in the core

There are other types of lower-level toggle which must be placed deeper within your architecture. These toggles are usually technical in nature, and control how some functionality is implemented internally. An example would be a Dev Toggle which controls whether to use a new piece of caching infrastructure in front of a third-party API or just route requests directly to that API. Localizing these toggling decisions within the service whose functionality is being toggled is the only sensible option in these cases.

Managing the carrying cost of Feature Toggles

Feature Toggles have a tendency to multiply rapidly, particularly when first introduced. They are useful and cheap to create and so often a lot are created. However toggles do come with a carrying cost. They require you to introduce new abstractions or conditional logic into your code. They also introduce a significant testing burden. Knight Capital Group’s $460 million dollar mistake serves as a cautionary tale on what can go wrong when you don’t manage your feature toggles correctly (amongst other things).

Smart teams view the Feature Toggles in their codebase as inventory which comes with a Carrying Cost, and seek to keep that inventory as low as possible. In order to keep the number of feature toggles manageable a team must be pro-active in removing feature toggles that are no longer needed. Some teams have a rule of always adding a toggle removal work item onto the team’s backlog when the toggle is first introduced. Other teams put “expiration dates” on their toggles. Some go as far as creating “time bombs” which will fail a test (or even refuse to start an application) if a toggle is still around after its expiration date. It’s a good idea to place a limit on the number of toggles a system is allowed to have at any one time. Once that limit is reached if someone wants to add a new toggle they will first need to do the work to remove an existing toggle.